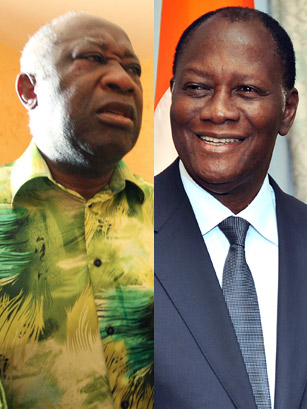

Elections in the Ivory Coast at the end of 2010 were supposed to herald a new era in this once prosperous West African nation, beset by more than a decade of civil strife. But incumbent President Laurent Gbagbo refused to accept the election's results — deemed legitimate by international and U.N. observers — and plunged the country into chaos. The coastal capital, Abidjan, became the domain of armed camps and militias; Gbagbo's opponent, Alassane Ouattara, sought U.N. protection in a prominent hotel and set up a shadow government. Clinging to power, Gbagbo invoked communal rhetoric, labeling Ouattara's supporters as "outsiders" in this ethnically-complex nation; as violence escalated, the U.N. felt compelled to intervene to stave off civilian massacres. In April, abetted by targeted U.N. and French strikes, Ouattara's forces and allied militia seized Abidjan and captured Gbagbo. The latter now faces war crimes charges at the International Criminal Court in the Hague. Ouattara has the unenviable task of righting Ivory Coast's listing ship — and must hope that further investigations into the massacres that took place during the conflict with Gbagbo don't yield ugly skeletons in his own closet.